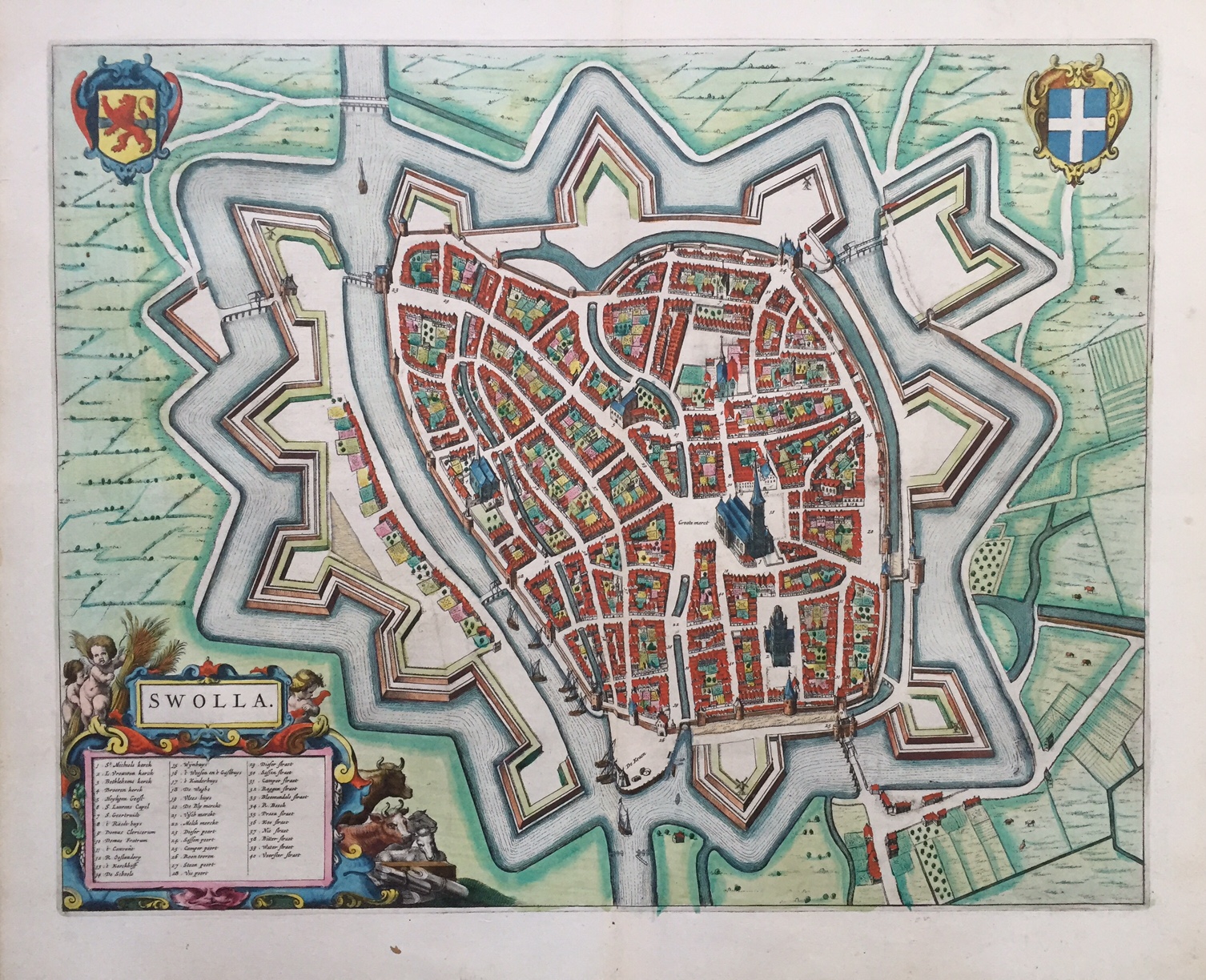

Zwolle

The city of Zwolle, currently capital of the Dutch province of Overijssel, was founded in the eleventh century. At the time, the area was ruled by the bishop of Utrecht, as part of the Holy Roman Empire’s ‘imperial church system’. Its name is derived from the word ‘suolle’, denoting a higher (sand) ridge raised above the surrounding marshland. By 1213, a group of people are already described as burgers or ‘citizens’ of Zwolle. The settlement quickly expanded, and by the fourteenth century the city became a religious and intellectual centre of the Devotio Moderna movement. When the first surviving demographical data become available, in the early modern period, Zwolle’s population fluctuated between 7,000 and 12,000 inhabitants.

Zwolle’s political and economic importance is reflected by its membership of the Hanse. Its merchants maintained contacts as far as Reval (modern Tallinn, Estonia). After the Dutch Revolt, however, its international commercial role was surpassed by cities in Holland such as Amsterdam. After some initial reluctance, in 1580 Zwolle joined the Union of Utrecht, being one of the three ‘voting cities’ in the States of Overijssel besides Deventer and Kampen, and regularly hosting their meetings. Spanish armies would never reconquer the city, unlike many others in the region. Zwolle was fortified with modern bastions, and continued to serve as a base of operations for the Dutch Republic’s forces. In the Disaster Year 1672, however, the city surrendered to the Bishop of Münster after the fall of Deventer, rather than risking a protracted siege. Zwolle eventually developed into a central node for both rail- and highway networks.

Georg Braun

Civitates orbis terrarum (1581)

< ‘A commonwealth so successful, such as neither Aristotle nor Plato ever described; insomuch that, due to opinion of its prudence and wisdom, immunities, singular privileges, and most righteous municipal laws, this Senate is, by other and neighbouring towns, in doubtful causes consulted, which also it doth judge and determine according to its own laws; and remits them ordered and ratified by judicial authority unto the places and towns round about.’ >

Law and Governance

On 31 August 1230, Bishop Wilbrand van Oldenburg officially granted the knights, aldermen, and common citizens of the village of Zwolle (milites, scabini et universus populus ville de Suolli) an urban charter that came with the right to construct walls and moats. Until 1294, a representative of the prince elected the city’s aldermen, but this official seems to have disappeared after that date. While the Overijssel cities needed the bishops of Utrecht to secure an urban charter, over the centuries they increasingly acted as semi-independent ‘Territorialstädte’. Deventer attempted to turn the Oversticht into a city state under her direction, but this was strongly opposed by the other cities. In 1341, Zwolle clearly demonstrated its independence by shifting the date on which the new college of aldermen would be elected from 22 February, as common in Deventer (the original source of its urban law), to 25 January. The city’s early modern printed urban law proudly opened with the statement: ‘Zwolle is a free city, that depends upon no other’. At the same time, the cities’ representatives met regularly with members of the nobility and the clergy at the diets of Overijssel (dagvaarten) to discuss regional matters. This cooperation was particularly active at the eve of the Dutch Revolt in the sixteenth century.

Zwolle’s urban law thus (incorrectly!) suggests that the Overijssel cities would have been independent ‘Reichsstädte’ or Free Imperial Cities, resorting directly under the Holy Roman Emperor. The clash between such pretensions and legal reality is revealed by a dispute that arose soon after the Dutch Revolt. In 1607, a discussion about sovereignty arose in the States of Overijssel between the representatives of the three cities and the nobility. The nobles argued that, in absence of a prince, the States enjoyed sovereignty as a collective. Even though in 1613, the States General formally agreed with the nobles’ position, Kampen, Deventer, and Zwolle neglected this judgment. For the next two centuries, they acted as if they were sovereign urban republics. In the surrounding countryside, the urban magistrates had to share power with the Overijssel nobility. Within the city walls, however, Zwolle’s regents ruled supreme.

Zwolle’s urban government had a dual structure: magistrates and meente (see: description picture below). All had to be at least 25 years of age, unless they were ‘doctores juris’. The meente had 48 members for life. Every year on 25 January, the feast of St. Paul’s conversion or ‘Pauli’, they elected 12 magistrates: the aldermen (schepenen). They had specialised tasks, with the two treasurers (cameraars) being most senior. All aldermen had to account to them for their expenses, which gave the cameraars a large degree of informal influence over urban government. Next came, in order of seniority, two grit masters (gruitmeesters), two inspectors (keurmeesters), two tile masters (tichelmeesters), two masters of public works (timmermeesters), and two toll masters (tolmeesters). Last year’s aldermen would become the 12 councillors (raden). Together, these men constituted the city’s daily government. By the eighteenth century, the number of aldermen and councillors had been reduced to 8 each. The magistrates’ office was a combined administrative and legal institution, as usual in premodern cities. Unlike in Western Dutch cities such as Amsterdam, Zwolle did not have a fixed burgomasters’ office. Every four weeks, two of the aldermen would serve as burgomasters, or ‘presidents’ of the urban government. According to Prak, this was meant to reduce the risk of- and incentive for corruption. When a burgomaster transgressed the civic norms for official conduct, his actions could already be corrected during the next month, and he would likely not be picked as magistrate in next year’s election.

The urban government met daily, even on Sundays. Decisions were made by majority vote. In case of a tied vote, in administrative matters the outcome was generally determined by lot. In important matters, however, a committee was formed. They would prepare a report based upon an investigation of retroacts, arriving at a recommendation that then formed the basis for the magistrates’ final decision. The council’s meetings appear to have been publicly accessible, as an intriguing urban bylaw dictates that persons outside of the council’s room were forbidden to talk about the subject that was discussed by the urban government.

The meente was more than just an electoral college. It had its own house and meeting room, next to the city hall. The body met at least three times per year until 1646, when this number was raised to five. Extra meetings were organised when necessary, however. Important decisions could only be taken if the meente concurred. For example, if the magistrates wished to implement new taxes, or discussed matters of war and peace, it had to request the meente’s approval. Usually, such decisions were prepared by a commission, in which two members out of each constituent quarter of the meente would be joined by two or four magistrates.

The meente also annually audited the city’s accounts, to ensure that the magistrates would handle the citizens’ common finances prudently. Two members of the urban government always attended meetings of the meente, as without their presence, no lawful decisions could be made. At least three out of four ‘streets’ or urban quarters represented in the meente had to agree to a proposal. In case of a tied vote, the magistrates’ opinion was decisive. Zwolle’s magistrates had a substantial number of urban offices at their disposal. In 1692, a committee produced an intriguing list of 98 unique ‘offices and subordinate positions dependent on this city’ (officien ende subaltern bedieningen van dese stadt dependerende).[1] The range of urban offices had continued to expand together with the scope of policy areas affected by the magistrates over the centuries. Physicians, midwives, barber-surgeons, and apothecaries offered burghers medical services; street-makers and builders constructed and maintained the town’s material public infrastructure; gate-keepers, criers, bailiffs, and executioners acted as the magistrates’ executive arm to keep security and peace; messengers maintained the flow of information and the legal and political relations with towns, rulers, and governments; and a variety of musicians and teachers educated and entertained the urban community.

Interestingly, the listed urban offices are divided into three ‘classes’. The ordering was not determined by the jobs’ content, but rather by who decided on their allocation. The entire urban government decided on offices of the first class. The second class was dealt with by one of its individual members by rotation, with their internal ranking being established by drawing lots. At the end of the resolution, all sixteen members of the urban government are listed in a numbered order. Thenceforth, any replacing magistrate would automatically receive the lowest position. The third class of offices would be filled by whoever occupied the position of president at the time of their vacancy. Intriguingly, not all of Zwolle’s urban offices appear to have been listed. It is noted that all offices and positions not specified as part of the three classes, would be ‘disposed of by them who of old and until now had been qualified to do so’. Only with the consent of the entire urban government, it would be allowed to ‘resign or leave’ an office of the second or third class. If the individual responsible for filling a vacant office did not do so within two weeks, or three weeks if he was traveling outside of the city, his turn would be considered to have past and the magistrates would collectively determine who would be selected to fill the current vacancy.

One of Zwolle’s crucial administrative offices was that of the urban secretaries. Our research has indicated that it was not always easy to fulfil this position with qualified candidates. In principle, Zwolle citizens were favoured over outsiders, especially for such sensitive and powerful offices. However, the Holt family, which delivered several candidates for the office from the late sixteenth century onwards, were originally foreigners. The fact that in this same period, Zwolle’s authorities provided educational stipendia for citizens’ sons to stimulate them to study at university, points at the challenge to find well-qualified personnel. The stipendia were granted on condition that the students would afterwards return to serve the urban community in a public office such as school master or secretary. Eventually, Zwolle was successful: the Holts and a number of other families continued to serve the city for decades, eventually becoming part of the urban elite themselves. Those interested in this and further stories about Zwolle’s secretaries, we kindly refer to the articles that can be found in the ‘sources’ section of this page below.

___________

[1] NL-ZlCO 0700, inv.nr. 72, p. 423-430. This list was edited and compared to similar but later registers of 1771 and 1794 in: J. C. Streng, ‘Stemme in staat.’ De bestuurlijke elite in de stadsrepubliek Zwolle 1579-1795 (Hilversum: Verloren, 1997), 454–59. Many offices consisted of more than one individual job, such as those of the four teachers (praeceptors) of the Latin School, or the forty-nine peat carriers.

Illustration: Johan ter Borch, Zilveren doosje met 14 keurbonen (1643), Historisch Centrum Overijssel / Collectie Zwolle.

As part of an attempt to create a typology of urban government in the Dutch Republic, authors have argued for the existence of ‘western’ and ‘eastern’ types. The presence of a meente or gesworen gemeente – ‘(sworn) representatives of the citizenry’ –is a unique aspect for cities in the east like Zwolle. This representative body was active from at least the fourteenth century, until the end of the ancien régime. As Streng points out, however, we should see this Dutch ‘eastern model’ as part of a much wider phenomenon in the Holy Roman Empire. Each of Zwolle’s four districts had 12 representatives, chosen for life. Every year on 13 December, the feast day of St. Lucy, open positions were filled through the curious procedure of a boongang (a procedure of drawing lots, in this case: (silver) ‘beans’). From every district, four keurnoten (voters) would be selected by drawing bi-coloured silver balls from a bag. Subsequently, the sixteen keurnoten would have to determine who would be selected as new members of the meente. Representatives who had participated in last year’s boongang, were excluded from drawing lots and could therefore not influence the present year’s election. In 1693, it was decided that if there were no vacant positions in the meente, there would be no boongang. This meant that all representatives could potentially join the next election.

Economy

Similar to many cities in the Low Countries, from the medieval period onwards Zwolle’s social and economic life were dominated by a broad range of merchant- and craft guilds. While the city’s craft guilds were often quite specialised, and therefore limited in their number of members, Zwolle’s oldest and most prominent merchant guild had as many as 249 members by 1639. It was called Sunternycklaesbroederschap, aptly named after St. Nicolas, patron saint of travellers and seafarers. It united all shippers, expediters, and diverse groups of larger and smaller traders.

In the late Middle Ages, Zwolle’s status as trading town was closely connected to its membership in the Hanse. This mercantile association had its origins in the twelfth century, when long-distance merchants from Westphalia, Saxony, the Low Countries, and the Southern Baltic had banded together to strengthen their position abroad. Since the members of this ‘community of interests’ (Interessengemeinschaft) were burghers of cities and in many places constituted the urban government, their economic cooperation also became political. In the fourteenth century, therefore, the Hanse formed as an organisation of traders and of towns that was particularly active in the exchange between the Baltic and the North Sea region. Its members profited from common privileges, and when their economic interests aligned, they were able to engage in collective political action.

For the early period, only sporadic evidence indicates Zwolle’s activities in the Hanse. At an unspecified time in the fourteenth century, the town even seems to have lost its membership, since, in 1407, a Hanseatic diet recorded Zwolle’s formal readmittance. From now on, Zwolle – together with the neighbouring towns of Deventer and Kampen – fulfilled an important connective function in the trade between Holland and the Hanse. Due to the growing competitions between the merchants of Holland and the Hanse, the transit-position of the Overijssel towns came with substantial potential for conflict. Thus, in 1470, the magistrates of Deventer, Kampen, and Zwolle refused to relocate their trade to Bruges, as had been decreed by a Hanseatic diet. While the council of Zwolle remained involved in Hanseatic politics well into the sixteenth century, the Hanse’s economic relevance for the town appears to have dwindled over time and definitively came to a stop during the Eighty Years’ War.

Well-situated at traffic routes along the rivers IJssel and Vecht, Zwolle’s merchants were particularly active in the exchange between the regions of Westfalia and the Northern Low Countries. Already in the fifteenth century, Zwolle and Amsterdam had concluded a bilateral toll treaty to stimulate commerce. Rye, wheat, ironware, textiles, wood, oxen, and sandstone were traded from the East. Especially in the early modern period, colonial wares arrived from Holland.

Henceforth, the city mainly profited from its geographical position between Holland and middle- and south-German cities, with goods being loaded on carts in Zwolle that travelled over the so-called Hessenwegen. While Zwolle’s merchants had some initial success in the trade in Bentheim sandstone, which flourished thanks to the construction boom in Holland after the mid-seventeenth century, they eventually lost this staple to their neighbouring rival town Hasselt. An important early modern trade for the Ijssel cities was the cattle trade. Large numbers of German oxen were transported to Zwolle, to fatten in the surrounding pastures before being sold to meat consumers in Holland. Apart from some instances of cattle plague, such as the crisis of 1719, this trade constituted a stable source of wealth for Zwolle from the Peace of Munster until the end of the ancien régime.

By the end of the eighteenth century, Streng characterises Zwolle as a ‘city of manufacturers, rather than merchants’. By 1795, 45% of the urban population worked in some form of craft or industry. Zwolle had a large textile industry, with the production of linen being most important. In 1640, the linen weavers’ guild had at least 164 members. This industry was closely linked to Holland markets, with production standards being closely aligned to those of Haarlem. Due to high wages in Holland, Haarlem merchants moved linen production to areas where cheaper production was possible. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Zwolle clearly profited from this development. In this same period, the city for a while also possessed a flourishing industry to produce pins and buttons.

Sources

- The best general history of Zwolle for this period is: J. ten Hove, Geschiedenis van Zwolle (Zwolle, 2005).

- A contemporary urban history up to 1691: B.J. van Hattum, Geschiedenissen der stad Zwolle I-IV (Clement & v. Santen, 1768-1773).

- For Zwolle’s legal and institutional history, see: F.C. Berkenvelder, Stedelijk burgerrecht en burgerschap in Deventer, Kampen en Zwolle (1302-1811) (Zwolle, 2005); J.C. Streng, ‘Stemme in staat’. De bestuurlijke elite in de stadsrepubliek Zwolle 1579-1795 (Hilversum, 1997); M. Prak, The Dutch Republic in the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge, 2023), chapter 10 (pp. 151-166).

- On Zwolle’s secretaries and other urban officials, see also: C. Manger and M. den Hollander, ‘Advisers or Decision-makers? The Agency of Dutch Urban Administrative Officials, c. 1500–1700’, BMGN 140-2 (2025), in press; C. Manger and M. den Hollander, ‘The Value of Work. Petitions and Public Servants in Zwolle, c. 1550–1700’, under review.

- For Zwolle’s economic history, see: E. Zoomer and C. Manger, ‘Kruimelsporen van de Hanze’, Overijsselse Historische Bijdragen 139 (2024), 55-73; F.C. Berkenvelder, Zwolle als Hanzestad (Zwolle, 1983); Job Weststrate, In het kielzog van moderne markten. Handel en scheepvaart op de Rijn, Waal en IJssel, ca. 1360-1560 (Hilversum, 2008); B. Looper, ‘De Nederlandse Hanzesteden: scharnieren in de Europese economie 1250-1550’, in: H. Brand en E. Knol (eds.), Koggen, kooplieden en kantoren. De Hanze, een praktisch netwerk (Hilversum, 2010), pp. 108-123.

- The most important archival collection on Zwolle’s urban government can be found in the Collectie Overijssel: 0700 Stadsbestuur Zwolle, archieven van de opeenvolgende stadsbesturen.

dr. Maurits den Hollander

Co-author

dr. Christian Manger

Co-author