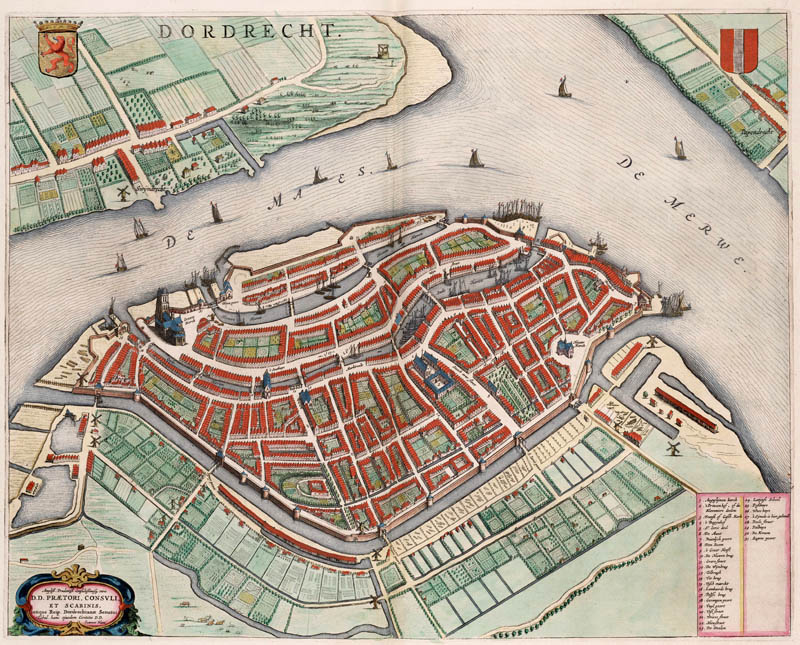

Dordrecht

Dordrecht is the oldest city in Holland. A charter granted to Dordrecht by Count Dirk VII of Holland in February 1200 has been preserved. Additionally, two documents dating back to 1220 refer to Dordrecht as an urban community with rights, duties, and a certain degree of jurisdiction. However, these early records build upon even older charters, likely originating around 1180. At that time, the city may have had about a thousand inhabitants, including at least a community of merchants and a fraternity of cloth cutters. Thanks to its central location in the Rhine-Meuse delta, Dordrecht quickly became an important commercial hub.

In the following centuries, the city grew significantly, aided by the staple rights it obtained as of 1299. These rights helped Dordrecht to develop into a major centre of trade, particularly in wine, timber, salt, stoneware, grain, and fish. By 1400, the city counted around 8,000 inhabitants, making it by far the largest city in Holland. A century later, the population had risen to approximately 11,000. During the ‘Dutch Golden Age’ in the seventeenth century, Dordrecht reached its peak size of around 21,000 inhabitants. However, economically, at that time the city was outpaced by competitors like Rotterdam and Amsterdam. From a governmental perspective, medieval Dordrecht was known for its close ties to the county, as well as the relatively strong influence of guilds on its urban governance.

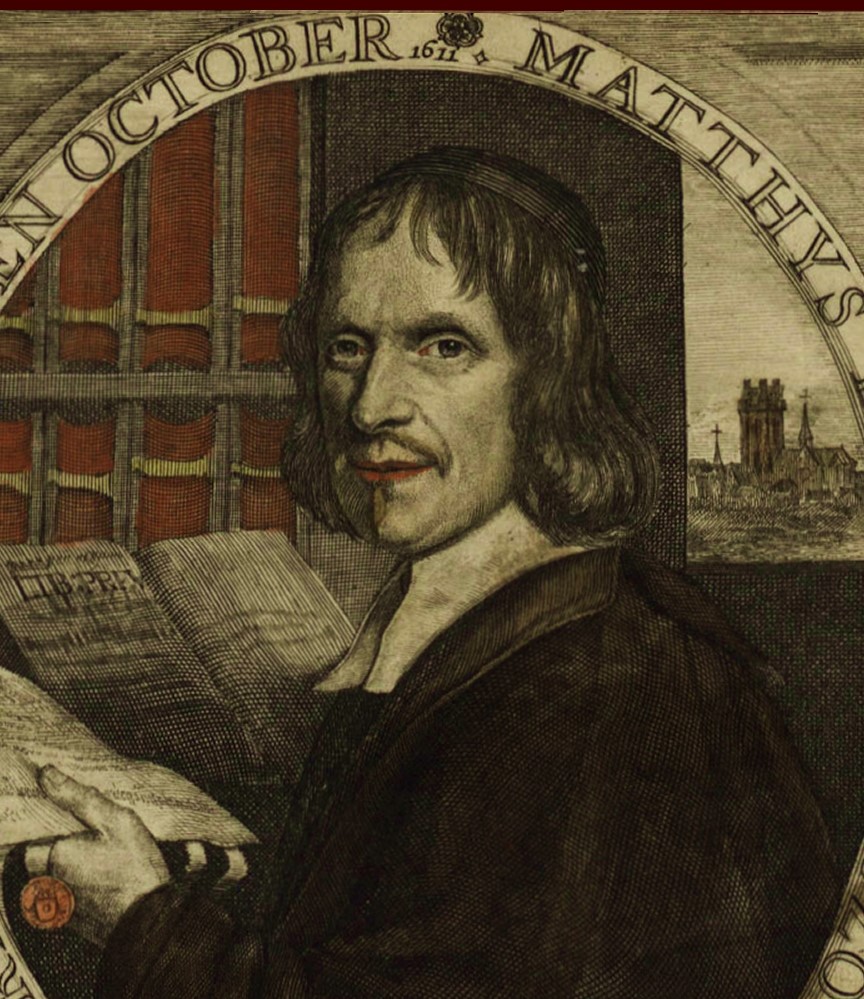

Matthijs Balen

Beschrijvinge der Stad Dordrecht (1677)

< ‘Here flows the liquid that can set the heart aflame,

When just a fresh sip sparkles bright within the glass.

Had Bacchus ever tasted the same,

He’d swear this was no wine, but nectar pure surpass.’ >

– C. de Bevere

Law and Governance

The emergence and development Dordrecht’s urban administrative structure make it clear that the count initially governed as his full property. For the period after 1200, Van Dalen has distinguished five administrative periods. The charter of 1200 issued by Count Dirk VII mentions an oppidum with scabini (aldermen), and the charter of 1220 proves the additional existence of both a bailiff (justicarius, iudex or later schout) and councillors (consilarii or later raden). The bailiff was primarily seen as the deputy of the count within the city, but the city held the right to request his replacement. There are indications that the bailiff (baljuw) of South-Holland was also involved in the city’s governance. The aldermen had the right to issue ordinances, and their jurisdiction was subjected to certain rules. Their jurisdiction probably functioned as court of appeal for several other cities as well, such as Schiedam (1275). However, it took another century before the first lawyers were found among the aldermen.

From 1285 onwards, the urban administration entered a second phase: in that year, two burgomasters were appointed. They were primarily responsible for financial matters and were selected without interference of the count. This marks the first civic engagement with the city’s government. In these years, we also encounter the first instances of administrative support by a clerk. The earliest mention is of the fittingly named Jan de Clerc in 1285. Additionally, external scribes were sometimes employed, such as a certain Andries, who received compensation that same year for drafting charters, composing a letter, and the sealing wax used as part of this work.

As the city grew, the influence of its guilds gradually increased. In 1293, a special provisional committee was employed to temporarily administer the city’s finances for the first time. It was in such committees, mostly dedicated to financial accountability or the preparation of urban legislation, that the first signs of guild influence emerged. After the death of Count Willem IV in 1345, it was decreed that masters of the craft guilds were required to be citizens of Dordrecht. In 1367, they gained formal representation when six of their representatives became part of a temporary twelve-member committee established by the city government to reorganise the city’s finances. From this moment onwards, they frequently took part in similar ad hoc committees. During this period, former aldermen and councillors also began to play a role in the city governance: they too were given representation in provisional committees, and were consulted on significant urban decisions, such as the regulation of the wine trade by foreign merchants in 1370.

The influence of the guilds reached its peak between 1386 and 1467, marking the third phase in the development of Dordrecht’s urban administration. During this period, three important governmental institutions were formalised. The first was the College van Goede Lieden van Achten (‘the Eight’) in 1366. This body followed the tradition of the ad hoc committees: it consisted of eight members, even though it had twelve votes in the decisions. This structure allowed them to be seen as representatives of the twelve so-called ‘key guilds’, which in turn represented all the city’s approximately 30 guilds. Later, all these key guilds held a key to the chest containing the city’s privileges in the town hall. The guild deans prepared a nomination of 24 candidates (six from each city quarter), from which the count of Holland selected eight members. Their primary responsibility was selecting the burgomasters, treasurers, and heemraden (home-advisors, local officials of the water board).

Shortly after the formation of the Eight, historical records begin to distinguish between the two burgomasters. One was elected three times a year by the community, while the other was appointed by the count. The latter effectively served as the chairman of the aldermen. This shift gradually changed the role of the burgomasters, placing less emphasis on financial administration and more on overall urban policymaking. Initially, the community-appointed burgomaster was not allowed to participate in the city council’s meetings, but this changed after 1434 (with some interruptions). From that year onward, two treasurers (tresoriers) were given permanent responsibility for managing the city’s accounts, after previously having been assigned this duty on an ad hoc basis.

In 1429, for the first time two clerks of the city are mentioned. They also worked for the treasury. A couple of years later, Jan van Zutphen first received an annual salary for his work. In 1445, one of the two clerks, Claes Schoenhout, often travelled abroad in order to represent the Dordrecht. He should be considered the first pensionary of Dordrecht. A year later, therefore, an extra secretary, Jan van Slingelant, was added to the city’s administrative support staff. However, the functions of pensionary and secretary were only formally separated from 1485 onwards.

Despite the establishment of the Eight and the advisory role of former aldermen and councillors, a need to consult the city’s ‘wealth and wisdom’ in certain issues persisted. In other Dutch cities, this led to the formalisation of a vroedschap. In 1456, Philip the Good granted Dordrecht a charter that established a Council of Forty (College van Veertigen). Two ducal councillors were tasked with selecting 100 citizens, from whom the guild deans would choose 40 to act as commissioners tasked with the appointment of aldermen and city councillors. In the first year of its existence, this Council of Forty would nominate five aldermen and two councillors. Additionally, they would propose a list of fourteen candidates, from whom the duke would select four aldermen and three councillors. The next year, the selection ratio would be reversed. Aldermen and councillors served two-year terms. This broad-based council was intended to mitigate the factional conflicts between Hoeken and Kabeljauwen.

However, this did not immediately succeed. Philip the Good was eventually forced to suspend the Council of Forty. It was only between 1467 and 1581 that Dordrecht’s urban government took on a stable form. At the top stood the bailiff (schout), nine aldermen (including the burgomaster on behalf of the count), five councillors, and the burgomaster on behalf of the community. The latter was elected by the Eight, but they were only allowed to select a former alderman or councillor – ensuring the preservation of the count’s interests. The Eight also selected the treasurers responsible for managing the urban finances. Of the two treasurers, one was called “van ‘t groot comptoir” (responsible for the city’s incomes) and the other “of the reparation”(responsible for the city’s expenses). In 1467, the Senior Council (Oudraad)was officially recognised as a governing body, and became consistently involved in the urban administration. In 1478, the Council of Forty was reinstated, though this time they were allowed to fill their own vacancies. Meanwhile, the city continued to rely on the advice of its wealthiest and most experienced citizens, as well as various ad hoc committees.

Nearly all of these institutions were supported by a clerk or secretary. The councils of Eight and Forty had their own secretary, there was a secretary for marital affairs, aldermen, and the so-called “water aldermen” (responsible for adjudicating maritime affairs) also had their own secretary. They all received a fixed salary. The general secretary was not allowed to be a member of the Senior Council. Sometimes these secretaries or clerks made changes to the regulations of Dordrecht on their own authority. The new keurboek of 1401 – compiled because the previous one had become illegible – contains, in any case, a strict penal provision against anyone who would make alterations in the book without prior consent of the bailiff, burgomasters, aldermen, councillors, the Senior Council, the Eight, as well as the deans of the guilds!

The Dutch Revolt did not significantly alter Dordrecht’s urban government. In practice, the Stadtholder took over the count’s role in the election of officials. The last phase of Dordrecht’s administration, until 1795, witnessed only a few changes. In 1652, the five councillors were abolished. In the same year, it was decided that the number of members of the Senior Councilshould be reduced to a fixed number of 40. And, finally, during the reign of Stadtholder Willem III (1672-1702), membership of the Council of Forty was no longer considered compatible with holding a position in the urban government (bailiff, alderman, or burgomaster).

Illustration: Anonymous, Drawing of the Crane Swartsenborch (c. 1570), Gemeentearchief Dordrecht

As early as 1273, Dordrecht had a crane. This is evidenced by the record of a dispute between the city’s citizens and the local wine carriers (wijnschroders), which mentions a fee for each barrel of wine handled by a crane. The wine cariers’ guild was a comital organisation responsible for loading and unloading wine, as well as operating the cranes and the windlass. The appointed officials had the work carried out by labourers who were later known as ‘crane children’ (kraankinderen).

Dordrecht was well known for its cranes. In a dispute from 1547, the wine carriers demanded double wages when wine unloaded at one crane had to be dragged past another crane. It was characteristic of Dordrecht that ‘the cranen standeth full nigh one to another, and though it be a small city, yet hath it four cranen, whereas many a greater town hath but one or two’. At its peak, Dordrecht indeed had four cranes for hoisting heavy goods from ships. As early as 1336, the Roodermond crane was built, and in 1408 it was relocated to the entrance of the Nieuwe Haven. Additionally, there was the Grote Rijnsche crane at the Oude Haven, the Kleine Rijnsche crane (or Swartsenborg) at the Wijnhaven, and the Kostverloren crane near the entrance of the Oude Haven on the river.

Economy

From the early thirteenth century onwards, merchants and cloth cutters were active in Dordrecht. Starting in the mid-thirteenth century, the count of Holland pursued a clear policy aimed at stimulating commerce, while also benefitting personally. For example, in 1240 he offered merchants from North German cities special protection, and in 1247 and 1284 he granted citizens of Dordrecht (partial) exemption from tolls on various products. On the other hand, in 1260, he sought to tighten his control over the wine trade by claiming the so-called schroodrechten for himself.

This policy proved successful. Dordrecht developed into the most important commercial city of Holland. It was a key link in both the north-south trade (between northern Germany and Flanders/France) and the east-west trade (between the Cologne/Rhine region and England). This made the city an attractive hub where supply and demand effectively aligned: a wide variety of goods was traded on its markets. In 1299, the count formalised this staple function. Goods transported via the rivers Lek or Merwede had to be brought to market in Dordrecht, regardless of toll exemptions. Toll officials in Geervliet and Strienemonde were instructed to allow goods’ passage only once ownership had changed hands in Dordrecht.

The staple rights served as tool for both the count and the city to increase their revenues. The count benefitted from higher toll incomes. Tolls and exchange fees (wissel) were collected in Dordrecht, where the local tollhouse essentially functioned as a checkpoint for the Geervliet toll. The city also profited from the increase in commercial activity. Merchants were required to use Dordrecht brokers (a municipal institution since 1284), or at least, to pay brokerage fees.

Unsurprisingly, other cities protested against these strict measures. Schoonhoven, along with several towns in North Holland, argued that their trading privileges predated the staple rights, and therefore prevailed. After a series of disputes, Count Willem III of Holland (r. 1304-1337) acknowledged this argument – except for the cases of wine (1330) and salt (1335). Soon afterwards (1339, 1344), the staple rights were extended to ships sailing upstream on the Meuse. By 1355, they applied to the Hollandse IJssel, the Rhine, the downstream Meuse, and the Waal as well. Historians generally regard this as the beginning of Dordrecht’s Golden Age. Nevertheless, Dordrecht faced strong competition, especially from Nijmegen, Gorinchem, Zierikzee, and Middelburg – cities that managed to secure specific exemptions from the staple rights.

Dordrecht explicitly perceived itself as commercial city. The Deductie of 1505 describes the economic function of various cities, stating that Dordrecht possesses no craft other than the regulation of the staple. This self-image fits within the spatial trade system described by Clé Lesger for the sixteenth century Low Countries. In this system, wine was the city’s driving commodity: Niermeyer estimated that during the 1380s around 3.3 million litres of German wine annually passed the city, of which 1.6 million litres changed ownership. Significant quantities of French wines were also traded in Dordrecht, despite this trade being a specialisation of Middelburg. Downstream, timber, iron, stone, and grain were imported while upstream, salt and fish were the most important goods. Dordrecht’s important shipping, shipbuilding, and barrel making (kuiperij) industries were closely tied to this river trade.

Despite the dominance of trade, the Dordrecht city government also attempted to encourage proto-industrial activity. Already in 1276 and 1277, wool weavers received various privileges. Between 1294 and 1295, the English wool payment office was even located in the city. Dordrecht later developed a cloth industry, though it seems to have been limited in its potential due to the conflicting interests of fishers and brewers, who depended on clean water. The fishing industry included both the transit of sea fish and the sale of freshwater fish. In this context, extensive salt refining industries developed near Dordrecht in the sixteenth century. At the time, the city counted around 22 breweries and also several wind mills. Despite these efforts, Dordrecht’s industry largely remained focused on trade and local consumption.

After the St. Elisabeth floods of 1421 and 1424, Dordrecht’s commercial activity came increasingly under pressure – particularly its passive trade was circumvented. Around 1500, the wine trade reached an all time low. Commerce recovered slowly afterwards, and flourished again by the mid-sixteenth century. Dordrecht then had a population of about 15,500 inhabitants. However, the city’s staple rights were increasingly the subject of disputes. Therefore, enforcement costs increased significantly, and in 1541 Emperor Charles V decreed that Dordrecht lost its rights on the Meuse staple. The Dutch Revolt brought another crisis, although the city once more experienced strong growth after 1585. Salt industry and iron trade, for instance, expanded rapidly. Nevertheless, economic historians agree that Dordrecht soon entered a period of relative decline, during which Rotterdam had surpassed Dordrecht as the dominant city of the region by 1630.

Sources

- There are several urban histories of Dordrecht. The contemporary standard work is M. Balen, Beschryvinge der stad Dordrecht (Dordrecht: Symen Onder de Linde, 1677). Useful modern histories include: J.L. van Dalen, Geschiedenis van Dordrecht (2 volumes), (Dordrecht: Morks, 1931-1933); J. van Herwaarden et al (eds.), Geschiedenis van Dordrecht tot 1572 (Hilversum: Verloren, 1996); W. Frijhoff et al (eds.), Geschiedenis van Dordrecht van 1572 tot 1813 (Hilversum: Verloren, 1998); H. ’t Jong, De oudste stad van Holland. Opkomst en verval van Dordrecht 1000-1421 (Utrecht: Omniboek, 2020).

- Still of great importance are the publications of J.F. Niermeyer, e.g. ‘Dordrecht als handelsstad in de tweede helft van de veertiende eeuw’, Bijdragen voor Vaderlandsche Geschiedenis en Oudheidkunde 1942-1943; ‘Een vijftiende-eeuwse handelsoorlog: Dordrecht contra de bovenlandse steden, 1442-1445’, Bijdragen en mededelingen van het Historisch Genootschap (Utrecht: Kemink, 1948).

- On Dordrecht’s staple rights, the work of B. van Rijswijk, Geschiedenis van het Dordtsche Stapelrecht (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1900), still contains the best general overview of the situation.

- There are several source publications on the city of Dordrecht. The most prominent are J.W.J. Burgers & E.C. Dijkhof, De oudste stadsrekeningen van Dordrecht 1283-1287 (Hilversum, Verloren, 1995); J.A. Fruin, De oudste rechten der stad Dordrecht en van het Baljuwschap Zuidholland (2 volumes) (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1882); P.H. van de Wall, Handvesten, Privilegien, vrijheden, voorregten, octrooijen en costumen midsgaders sententien, verbonden, overeenkomsten en andere voornaame handelingen der stad Dordrecht (5 volumes) (Dordrecht: Van Braam, 1770-1775).

- On city councils in Holland (including useful information on Dordrecht), see E. Eibrink Jansen, De opkomst van de vroedschap in enkele Hollandse steden (Haarlem: Amicitia, 1927).

- On the economic conjuncture of Dordrecht in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, useful information can be found in T.S. Jansma, ‘De betekenis van Dordrecht en Rotterdam omstreeks het midden der zestiende eeuw’, in: Jansma (eds.), Tekst en uitleg (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1974); P.W. Klein, De Trippen in de 17de eeuw. Een studie over het ondernemersgedrag op de Hollandse stapelmarkt (Assen: Van Gorcum, 1965).

- For the place of Dordrecht in the economic structure of the Low Countries see e.g. J. Dijman, Shaping Medieval Markets. The Organisation of Commodity Markets in Holland, c. 1200-1450 (Leiden: Brill, 2011) and C. Lesger, Handel in Amsterdam ten tijde van de Opstand (Hilversum: Verloren, 2001).

dr. Marco in ‘t Veld

Author