Amsterdam

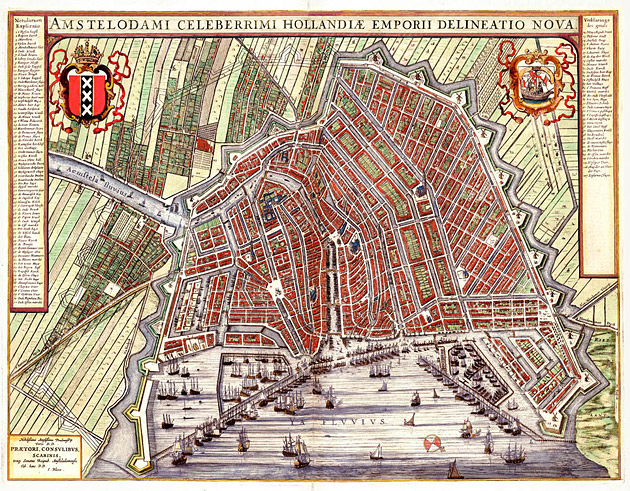

In 2025, the city of Amsterdam proudly celebrates its 750-year anniversary. This is connected to the oldest surviving written record mentioning Amstelredamme, a privilege dated 27 October 1275. On this day, Count Floris V of Holland granted toll-freedom to the inhabitants of the small town which had sprung up on both ends of the dam that protected the region of Amstelland from the waters of the river IJ. Around 1300, Amsterdam supposedly received its first town charter, but since this document has not been preserved the date of the toll privilege is generally held as the birthday of what would one day become a bustling commercial hub with global impact.

In 1578, the year of its ‘Alteratie’ or ‘revolution’ from Catholic to Protestant ruling elites as part of the Dutch Revolt against their Habsburg sovereign Philip II of Spain, around 30,000 inhabitants lived within Amsterdam’s walls. In the following decades, this number would quickly explode. Migration streams of wealthy Protestant traders from cities like Antwerp in the Southern Netherlands, Sephardic Jews from the Iberian Peninsula, as well as sailors and workers from the neighbouring German and Baltic regions, all contributed to make Amsterdam the cultural and economic centre of the Dutch Golden Age. By the early eighteenth century, the city housed about 200,000 people from all corners of the world. In 1808, Amsterdam was formally declared the capital of the new Kingdom of Holland under Louis Bonaparte.

Isaac Le Long

De Koophandel van Amsterdam (1714)

< ‘Amsterdam is, at this present, without contradiction, the most renowned mercantile city of all Europe; a City which, though it may not boast of any exceeding antiquity, yet in its newness is far happier than many elder and formerly illustrious Towns. For truly, there seemeth in these days none that may well be compared unto it, whether in greatness and fair convenience of place, or in the multitude of people, riches, trade, and the abundant navigation of ships, to and from all the corners of the world.’ >

Law and Governance

Amsterdam’s oldest town charter was granted by the Utrecht Bishop Gwijde van Avesnes around 1300, probably prompted by the citizens’ own initiative. Such a charter essentially ‘created’ the urban jurisdiction, lifting the city out of the surrounding countryside. Like any other legal district, the city was governed by the sheriff (schout) and seven aldermen (schepenen). Soon, the aldermen were joined by four burgomasters (burgemeesters). Together, they formed the urban magistrate, which came to possess the right to issue the local bylaws (keuren, ordonnantiën) that regulated the citizens’ life and work. Every year, once the new burgomasters and aldermen had been elected on 2 February, they formally ‘renewed the law’ through an announcement from the city hall’s proclamation gallery facing Dam Square. In medieval and early modern Amsterdam, there was no separation of powers: the urban magistrate was responsible for the creation of laws and policies as well as their application.

Until the Alteratie, the sheriff represented the sovereign, the Count of Holland. He acted as chief prosecuting officer and guarded the public ‘peace’. He also presided over the urban court (the aldermen’s bench). The aldermen, whose number was expanded to nine in 1560, primarily concerned themselves with the administration of justice. Originally, the burgomasters had primarily concerned themselves with urban finances and public works, but soon they came to occupy the central executive position in urban government. The burgomasters had the right to appoint candidates to a wide range of urban offices, which rapidly expanded to number over 2,000 by the eighteenth century.

Besides the urban magistrate, Amsterdam also had a council representing the ‘wisdom’ of the city: its vroedschap. The council itself filled vacant positions by majority vote, co-optation. Once elected, one would be a member for life. Originally consisting of 24 members, in 1477 Mary of Burgundy had expanded the city council to 36. In that same year, the City Council received the privilege to annually nominate 14 candidates (from 1560: 18), from which the sovereign or his stadtholder would select that year’s aldermen. In practice, the burgomasters added a small mark behind the names of the candidates who they wished to be elected, a demand that was normally followed. The burgomasters sought the advise of the City Council in all important matters of government. This included the raising of taxes, for instance, but also matters of (inter)national politics. At the end of the day, however, the burgomasters dominated Amsterdam’s politics.

In part, this was related to Amsterdam’s privilege to elect its own burgomasters, without interference from the sovereign or their representative. This right had been granted by Duke Albrecht of Bavaria in 1400. In other cities in the County of Holland, the City Council would draw up a list of candidates from which the sovereign would select the new burgomasters, similar to the procedure through which the aldermen were elected. In Amsterdam, the burgomasters were elected by the Large Senior Council (groote oud-raad), consisting of all former burgomasters and former aldermen. The results of this annual election were pre-negotiated in what was informally known as the ‘great intrigue’ (groote cuyp). This resulted in a small circle of regents dominating urban politics. By the eighteenth century, the total number of acting and former burgomasters fluctuated between 9 and 12 individuals at any given time.

From 1578 onwards, the burgomasters increasingly concerned themselves with national and international politics rather than with the details of the city’s daily management. From the late sixteenth century, the burgomasters appointed the sheriff, and during Stadtholderless Periods (1650-1672 and 1702-1747) they also appointed the aldermen themselves.

The rapid growth of Amsterdam, as well as its magistrate’s responsibilities in this period, necessitated an expansion and professionalisation of urban government. By the seventeenth century, three councils of Treasurers had taken over the financial management of the city from the burgomasters. The Orphan Masters took over their responsibility for the administration of orphans’ estates. Similarly, a series of ‘subaltern’ courts was created to alleviate the aldermen’s burden: the Chamber of Marital Affairs (1578), the Chamber of Insurance and Average (1598), the Chamber of Small Affairs (1611), the Chamber of Maritime Affairs (1641) and the Chamber of Insolvent and Abandoned Estates (1643). An expanding number of urban secretaries formed the crucial information link between the burgomasters, external contacts, and the rest of the urban government and its administrative officials. Together with the pensionaries, the city’s academically trained legal advisers, they could influence urban policy behind the scenes. This informal power in part resulted from their information position, but was also aided by their long-term presence at the top of Amsterdam’s urban hierarchy.

Illustration: Gerrit Berkheyde, Het stadhuis op de Dam in Amsterdam (1672), Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Currently in use as Royal Palace, Amsterdam’s City Hall designed by architect Jacob van Campen is generally considered to be one of the most important historical and cultural masterpieces of the seventeenth century. By the time its construction started in 1648, Amsterdam’s government and bureaucracy had clearly outgrown its late medieval predecessor. In 1652, a fire consumed the old building, and in 1655 the first floors of Van Campen’s magnificent design were officially opened by the proud burgomasters. The glorious central Citizen’s Hall (Burgerzaal) was surrounded by marble galleries, which provided access to the multitude of courts and offices from which Amsterdam was ruled in the early modern period. At the building’s centre, two large world maps are displayed on the floor, signifying Amsterdam’s position as world power: its urban oligarchy (the regenten) dominated Dutch international politics by virtue of their great wealth, and were well-aware of their stature and influence.

Economy

In the eighteenth century, Amsterdam’s official ‘urban historian’ Jan Wagenaar described three sources of its commercial wealth: (1) the trade in- and production of goods and services related to that what is consumed by the city and its inhabitants, (2) the activities related to the transportation of goods within the Dutch Republic, and (3) activities related to international trade and transport.

From the origin of the city onwards, it is believed to have possessed the right to organise a number of public markets. Daily markets were organised for the sale of food and other daily consumptive necessities, milk even being sold on Sundays. The oldest weekly market seems to have been organised on Mondays; later Wednesday- and Friday-markets were added. Three large annual free-markets were organised at mid-Lent, Pentecost, and the large September Kermis. The names of various streets and squares in Amsterdam still hint at the locations of the many specialised markets that were organised in the medieval and early modern city. Of course, Amsterdam possessed an extensive network of shops and retailers, where a diverse range of goods could be bought outside of the markets’ context. Together with the urban industries, most of their work was regulated by a swiftly expanding number of craft guilds. It is estimated that by the later seventeenth century, more than 70% of male Amsterdam citizens worked in a sector that was regulated by a guild. A number of important industries such as those of the brewers, soap-makers, and sugar refiners did not have a guild, but nevertheless displayed corporate characteristics in their organisation. Guilds organised labour, but also came with social welfare arrangements such as burial funds or even old-age pensions. It has therefore been argued that the necessity to join a craft guild was an important motive to obtain Amsterdam citizenship.

Citizenship was also intimately connected with Holland’s internal trade and the transport sector. The 1275 privilege of the Counts of Holland granted all Amsterdam citizens freedom from tolls. This stimulated the rise of merchants, as well as facilitating institutions. An example is the Amsterdam weighing house (waag), situated on the Dam close to the old harbour. Merchants were obliged to deliver their goods there, both to determine the import tax rate, as well as to prevent fraud. In exchange for a fee, it was also possible to deliver large parties of goods straight to the seller’s warehouse, where staff of the weighing house would supervise the proceedings.

Over the early modern era, Amsterdam came to be connected to all important cities in Holland and the wider Republic through a network of barges and a line shipping system (beurtvaart). This combination of public transport and packet trade was so efficient that it even delayed the construction of railroads in the northern Netherlands.

Amsterdam’s international trade, finally, was the prime source of its early modern economic efflorescence. When subsidence of soil made the Holland polders too wet for the production of grain in the late medieval period, the citizens of Amsterdam became increasingly involved in a large scale grain trade. The trade in bulk goods such as grain, fish, and wood with the Baltic was the foundation of Holland’s large and most competitive trade fleet, and was aptly named ‘the mother of all trades’ (moedernegotie). By the end of the sixteenth century, the Dutch Revolt had caused widespread destruction in the big Flemish cities. Merchants from Antwerp, the prime commercial hub of the sixteenth century, increasingly relocated to Amsterdam. Together with local traders, they expanded its trade to span the entire globe. From 1602, the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) coordinated the trade in spices and Asian luxuries, while after 1621 the Dutch West India Company (WIC) engaged in the triangular trade and colonisation in West-Africa and the Americas.

A range of important legal and economic institutions supported Amsterdam’s international trade. In 1609, the Bank of Exchange (wisselbank) made the city into a global financial centre. Its main purpose was to move the organisation of money transfers away from the rather unregulated private markets and to bring them under the public control. From 1611, the Exchange (beurs) designed by Hendrick de Keyser provided protection from the elements for all traders, both those dealing in physical and ‘virtual’ goods – think of the revolutionary trade in VOC shares. Even though Amsterdam’s trade saw relative decline in the eighteenth century, it was not until the Napoleonic era that it was surpassed by its European competitors.

Sources

- The best general histories of Amsterdam for this period are volumes I and II of: Marijke Carasso-Kok et al. (ed.), Geschiedenis van Amsterdam (SUN, 2004-5); as well as, still: Jan Wagenaar, Amsterdam (1760-7).

- For Amsterdam’s general legal and institutional history, see chapter 7 of: Marco in ‘t Veld & Erik-Jan Broers, Recht tussen staat en samenleving (Boom, 2024); Maurits den Hollander & Bob Wessels, Palace of Commerce. Amsterdam’s City Hall in the Seventeenth Century (Verloren, 2025).

- On the Amsterdam court: Marco in ‘t Veld, Commerce and Customs in the Courts. A comparison of mercantile customs, jurisdictions and institutions in Amsterdam and Lyon (early 18th century) (PhD: Vrije Universiteit Brussel, 2022). Useful to understand contemporary legal documents are formularies like: Willem van Alphen, Papegay (1682).

- Some subsidiary courts and institutions have been the subject of detailed studies. On the Orphan Masters: Josje Schnitzeler, Financial care for the vulnerable. Rise and decline of Holland orphan chambers (PhD: Utrecht University, 2022). On the Desolate Boedelskamer: Maurits den Hollander, Court, Credit, and Capital. Amsterdam’s Insolvency Legislation in the Dutch Golden Age (CUP, 2025: forthcoming). On the Chamber for Insurance and Average: Sabine Go, Marine Insurance in the Netherlands 1600-1870: a comparative institutional approach (AUP, 2009).

- For Amsterdam’s economic history, see amongst others: Oscar Gelderblom, Cities of Commerce. The Institutional Foundations of International Trade in the Low Countries, 1250-1650 (Princeton University Press, 2013); Clé Lesger, Handel in Amsterdam ten tijde van de Opstand. Kooplieden, commerciële expansie en verandering in de ruimtelijke economie van de Nederlanden ca. 1550-ca. 1630 (Verloren, 2001). On its global commercial connections, see: Piet Emmer & Jos Gommans, The Dutch Overseas Empire, 1600-1800 (CUP, 2021).

- Some economic institutions have been the subject of detailed studies. On the Bank of Exchange: Pit Dehing, Geld in Amsterdam. Wisselbank en wisselkoersen, 1650-1725 (Verloren, 2012). On the share trade: Lodewijk Petram, The World’s First Stock Exchange (Columbia University Press, 2014). On the beurtschippers: Jan de Vries, Barges and Capitalism: Passenger Transportation in the Dutch Economy, 1632-1839 (HES Publishers, 1981).

dr. Maurits den Hollander

Author