Cologne

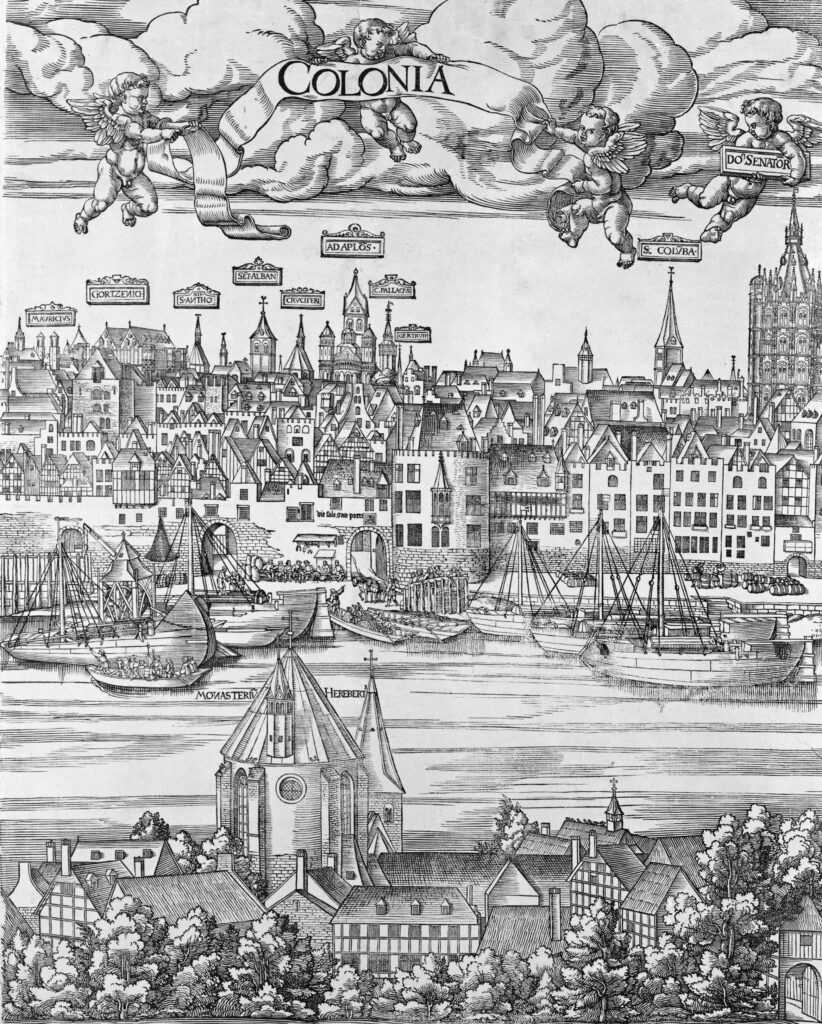

With its highly advantageous location on the Rhine River and strong ties to interregional urban networks, Cologne was a significant European trade node in the late medieval and early modern periods. The city had circa 35,000-40,000 inhabitants in the fifteenth century, making it the largest city in the northern German region. After 1288, Cologne successfully claimed political independence from its overlord, the Archbishop, and in 1475, it obtained the status of a free imperial city (Freie Reichsstadt) within the Holy Roman Empire. This meant that Cologne was a direct subject of the emperor rather than a regional ruler, and it could therefore maintain a relatively strong urban autonomy. Additionally, the city was a prominent member of the Hanse, a cooperation of northern-European cities that had obtained – and fiercely protected – shared trade privileges and freedoms in foreign regions.

Cologne similarly held an influential cultural and religious position. In 1388, the University of Cologne was founded, making it the fourth one in the Holy Roman Empire after Prague, Vienna, and Heidelberg. The city was also an important centre of pilgrimage after it obtained the relics of the Three Wise Men and subsequently built the Shrine of the Three Kings in its cathedral – although the construction of the Cologne Cathedral itself remained unfinished in the Middle Ages, leading the crane which remained on its tower to become an easily recognisable landmark on early modern maps.

The sixteenth century marked a period of change and transformation for Cologne, as the city faced significant political and cultural shifts. These changes were shaped by both internal dynamics and broader developments across Europe, including the Reformation, the centralisation politics of the Habsburg monarchy, and the evolving nature of European trade.

Hartmann Schedel

Liber Chronicarum (1493)

< ‘Also admirable is how much hope and civic-mindedness are there in that city; and how much seriousness the men possess, and how much elegance the women have. Franciscus Petrarch writes of an old custom of the people of Cologne that was especially observed by the common women. At sundown on the Eve of St. John the Baptist an incredible number of women assemble on the banks of the river; and with sleeves rolled up to their elbows, they immerse pleasant smelling herbs in the water, and put their snowy white hands and arms in it, at the same time throwing all the troubles of the year into the water, so that the river may wash them away and bring back happiness instead. Oh, you more than blessed inhabitants of the Rhine, which washes away and cleanses your shortcomings, something which neither the Danube (Hister) nor the Elbe (Albis) in Upper Germany, nor the Po (Padus) in Italy, nor the Tiber ever has the strength to do. These are rather lazy, sluggish rivers!’ >

Law and Governance

Initially, the city was a part of an ecclesiastical principality (Hochstift) in the Holy Roman Empire, led by the Archbishop of Cologne in his position as the prince-elector (Kurfürst). Tension between the ruler and the urban community (Gemeinde) arose in the early medieval period as wealthy burghers sought to protect their own interests (such as privileges and trade monopolies) in the city, apart from the Archbishop’s influence. Matters escalated during the Investiture Controversy in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, when, as noted by Huffman, “Cologne burghers showed remarkably expanded collective agency by interjecting themselves into the controversy”. For instance, one of the leading parties of the Investiture Controversy, Emperor Henry IV, officially recognised the Gemeinde as a legal authority. Similarly, his successor, Henry V, also negotiated with the city of Cologne without the interference of the Archduke. After Archbishop Siegfried II suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Worringen in 1288, Cologne’s urban community managed to claim official political independence. While the Archbishop remained the lord of the city (until it became a free imperial city in 1475), his influence was reduced to appointments for the high court and, in the fifteenth century, he moved his seat to the nearby city of Bonn.

Furthermore, Cologne’s political structure was significantly impacted between 1391 and 1396, when the rising new merchant class revolted against the ruling patriarchy and claimed dominance over the urban council. During the early medieval period, wealthy citizens (the Patrizier families or the meliores, the self-proclaimed ‘better people’) and ministeriales took on the role of Schöffen (also called scabini) in the city, lay-judges who also had seats in the Archbishop’s High Court. From 1369 onwards, the urban council was dominated by members of prominent merchant families and the urban guilds. The 22 so-called Gaffeln, associations of burghers based on their occupation, elected the majority of the urban council members. The Gaffeln encompassed a wide spectrum of economic activities, including craft guilds, for example, tailors, shoemakers, and bakers, and merchant guilds, such as the Rhenish wine merchants. Each Gaffel was entitled to send a fixed number of representatives, ensuring that political power was more evenly distributed among the city’s economic sectors. They elected 36 individuals in total, with 13 other magistrates (the Gebrech) chosen by the urban council itself. Lastly, two burgomasters, elected from different Gaffeln, led the council for one year at a time. The burgomasters functioned as the chief representatives of the city, both internally and externally. Internally, they presided over council meetings and oversaw the execution of council decisions. They were also responsible for supervising the city’s finances, legal affairs, and public order, often working closely together with the urban secretaries and other officials. Externally, the burgomasters represented Cologne in negotiations with imperial authorities, neighbouring cities, and the Archbishop. They led diplomatic embassies, signed treaties, and handled diplomatic correspondence.

Urban secretaries (or scribes) also played a crucial and increasingly professionalised role within Cologne’s urban government. The day-to-day functioning of the council relied heavily on university-trained bureaucrats. The secretaries formed the administrative backbone of Cologne’s civic government, handling documentation, correspondence, legal matters, and record-keeping. Urban secretaries had often enjoyed a university education, frequently comprising legal training in Roman or canon law. Thanks to their often long-term positions, they helped maintain internal administrative continuity, which was especially important given the annually rotating offices of council members and the shared governance among the Gaffeln. Though technically subordinate to the council, experienced secretaries could wield considerable informal influence. Their knowledge of procedure, precedent, and law often meant that they shaped the formulation of council decisions. Some even held overlapping roles as notaries or legal advisors.

As a result of its political independence from the Archbishop, its position as a free and, later on, imperial city and its membership of the Hanse, Cologne had significant autonomy and influence. Within the organisational structure of the Hanse, Cologne was the leader of its own regional quarter, which included cities such as Münster, Wesel, Nijmegen, and Deventer. Additionally, the city joined various other urban bonds, such as the Rhenish League (Rheinischer Städtebund) in the second half of the thirteenth century. Such often overlapping city leagues, protecting specific shared interests, were part and parcel of the medieval period.

With Cologne’s many urban connections and internal cooperations between the merchant class and guilds, its burghers could access various courts, with only some limited boundaries between these legal spaces. An inhabitant of Cologne who had obtained citizenship could access the urban council’s court, but also the courts of the city’s guilds, the Archbishop, and the Holy Roman Empire (the Reichkammergericht). Thanks to their city being part of the Hanse, burghers involved in trade could also access other urban courts within the League, or turn towards the Hanseatic outposts (Kontore) in foreign trading regions.

Cologne’s urban court, led by its council members, heard cases that typically involved disputes among citizens, such as issues of property and inheritance, contracts, or other commercial transactions. The council also handled public order cases, including cases of theft and assault. While the council served as the final court of appeal in many cases, it often delegated legal tasks to specialised courts or judges for specific types of cases. For many legal matters, Cologne relied on the Schöffengericht, who, since 1296, were elected among the burghers, every half year, by the council. These judges would hear a broad range of cases, including criminal trials and some civil disputes. While the Schöffen were not trained legal professionals, they were respected citizens whose judgments were based on customary law and local ordinances. The presence of both councillors and Schöffen in the courts ensured that legal decisions reflected both the community’s customs and the urban council’s policies.

As a significant religious centre, Cologne also had ecclesiastical courts, which dealt with matters concerning canon law. These courts were separate from the city’s municipal courts and had jurisdiction over religious matters, including marriage disputes, inheritance issues involving clergy, and cases of heresy or moral conduct. The Archbishop of Cologne, as the city’s spiritual leader, had authority over these courts, though his influence was typically limited to matters within the church’s domain. Furthermore, since Cologne was a Free Imperial City, it was subject to the broader legal framework of the Holy Roman Empire. This meant that certain high-profile cases, especially those involving nobles, were heard by imperial courts. The Reichskammergericht was established in 1495 by Emperor Maximilian I as the principal imperial court for the Holy Roman Empire, tasked with resolving disputes among the empire’s various territories. It had both civil and criminal jurisdiction, addressing issues that were too complex or significant to be handled by local courts. As the highest judicial body in the Empire, the Reichskammergericht was empowered to hear appeals from lower courts and to arbitrate in legal matters involving the empire’s nobility, cities, and ecclesiastical authorities.

Economy

Throughout the medieval and early modern period, Cologne’s merchants were active on both local and international markets, facilitating the exchange of goods and fostering the city’s economic growth. Cologne’s location on the Rhine made it an essential trading hub in North-Western Europe. The city was strategically positioned at the crossroads of major trade routes connecting the North Sea, the Baltic, Flanders, Brabant, and Italy. Due to the city’s guest law (Gastenrecht), foreign merchants could only trade with the assistance of a Cologne burgher. Cologne’s own merchants engaged in the exchange of a wide variety of goods, including wool, wine, cloth, herring, salt, grain, and spices. Being one of the first German groups to obtain privileges in England and the Low Countries – before grants from the local rulers, mainly for convenience, had grouped merchants who spoke Low German together as the so-called ‘Hanse’ – Cologne’s urban council maintained strong political ties with these regions throughout the medieval and early modern period. In particular, as part of the cloth trade, Cologne’s merchants mainly divided their English trade businesses between London and Antwerp. In the latter city, Cologne merchants set up a long-lasting system of buyers, representatives, and sellers, moving goods to England and exporting others from Antwerp’s harbour deeper inland.

Due to its Rhenish wine staple, Cologne was also a mandatory stop for merchants and skippers transporting wine barrels from the Rhine region to the markets of, among others, Dordrecht, Antwerp, and Bruges. Here, the urban infrastructure also played an important part, in particular Cologne’s circa 1 kilometre long harbour, which allowed access to increasingly large ships that traversed the Rhine, as well as witnessing the implementation of several cranes.

Cologne’s involvement in the wine trade was closely tied to the Middle Rhine and Moselle regions, which were famous for producing high-quality wines. Municipal authorities regulated the wine trade through strict market controls and toll systems. Imported wines were subject to inspection and customs duties upon arrival at Cologne’s ports. The city also maintained detailed records of wine shipments and prices, which helped stabilise the market and provided revenue for the urban administration.

Seasonal wine fairs attracted regional traders and allowed Cologne to assert economic dominance in the Rhine corridor. Several of the city’s Gaffeln were directly or indirectly involved in the Rhenish wine trade, reflecting the trade’s economic significance and the city’s corporative structure. Among the 22 Gaffeln, we can discern the wine merchants and the shippers guild, two groups that were most directly engaged with the trade and distribution of wine; the coopers’ guild, responsible for producing and maintaining barrels for storage and transport; and the innkeepers’ guild, whose members bought wine in bulk to sell to their visitors.

In addition, the city also benefited from its thriving textile industry. In the medieval period, Cologne became a significant producer of cloth, particularly woollen textiles, which were in high demand across Europe. This industry attracted skilled labourers and artisans from across the Holy Roman Empire, and Cologne’s textile production became an essential part of its economic fabric. Cologne’s prominent economic position can also be gleaned from the widespread implementation of its commercial weights and measurements (the Cologne mark) in other cities of commerce.

From the late sixteenth century onwards, Cologne’s previously leading role within European trade began to decrease slightly. Several factors contributed to this decline in prominence, in particular the growing significance of transatlantic trade and the subsequent rise of competing commercial centres. Although the city’s trade in Rhenish wine remained strong, it suffered from inflation, and its customer base began to shrink, with Rhenish wine becoming more of a luxury product. Additionally, historians have noted the rising popularity of beer consumption, thanks to the newly introduced use of hops in its production.

Sources

- For works on the history of medieval and early modern Cologne, and the development of its urban council, see, in particular: Bernd Dreher, Texte zur Kölner Verfassungsgeschichte, Veröffentlichungen des Kölnischen Stadtmuseums H. 6 (Cologne, 1988); Wolfgang Herborn and Carl Dietmar, Köln im Spätmittelalter. 1288–1512/13, Geschichte der Stadt Köln Band 4 (Cologne, 2019); Joseph P. Huffman, Medieval Cologne From Rhineland Metropolis to European City (A.D. 1125–1475) (Berlin/Boston, 2025) (quote from p.6); Bruno Kuske, Köln, der Rhein und das Reich – Beiträge aus fünf Jahrzehnten wirschaftsgeschichtlicher Forschung (Graz/Cologne, 1956).

- Relevant studies that touch upon the subject of Cologne’s commercial position in the medieval and early modern period, and especially the Rhenish wine trade, are: Franz Irsigler, Die wirtschaftliche Stellung der Stadt Köln im 14. und 15. Jahrhundert: Strukturanalyse einer spätmittelalterlichen Exportgewerbe- und Fernhandelsstadt, Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftgeschichte nr. 65 (Wiesbaden, 1979); Raymond van Uytven, ‘Die Bedeutung des Kölner Weinmarktes im 15. Jahrhundert’, Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter, 30(1965). Also of interest are the discussions regarding Cologne’s Rhenish trade in Job Weststrate, In het Kielzog van Moderne Markten. Handel en scheepvaart op de Rijn, Waal en IJssel ca. 1360-1560 (Hilversum, 2008), and ibidem, ‘The organization of trade and transport on the Lower Rhine and Waal rivers around 1550’, in: Hanno Brand (ed.), Trade, diplomacy and cultural exchange. Continuity and change in the North Sea area and the Baltic c. 1350-1750 (Hilversum, 2006).

- For insight into Cologne’s legal history, see, in particular: Franz-Josef Arlinghaus, Inklusion–Exklusion. Funktion und Formen des Rechts in der spätmittelalterlichen Stadt. Das Beispiel Köln, Norm und Struktur / Studien zum sozialen Wandel in Mittelalter und Früher Neuzeit, Band 48 (Cologne, 2018).

- For further insight into the Hanse: Hanno Brand and Egge Knol (eds), Koggen, Kooplieden en Kantoren. De Hanze, een praktisch netwerk (Hilversum, 2010); Justyna Wubs-Mrozewicz and Stuart Jenks (eds), The Hanse in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (Leiden/Boston, 2013).

Ester Zoomer MA

Author