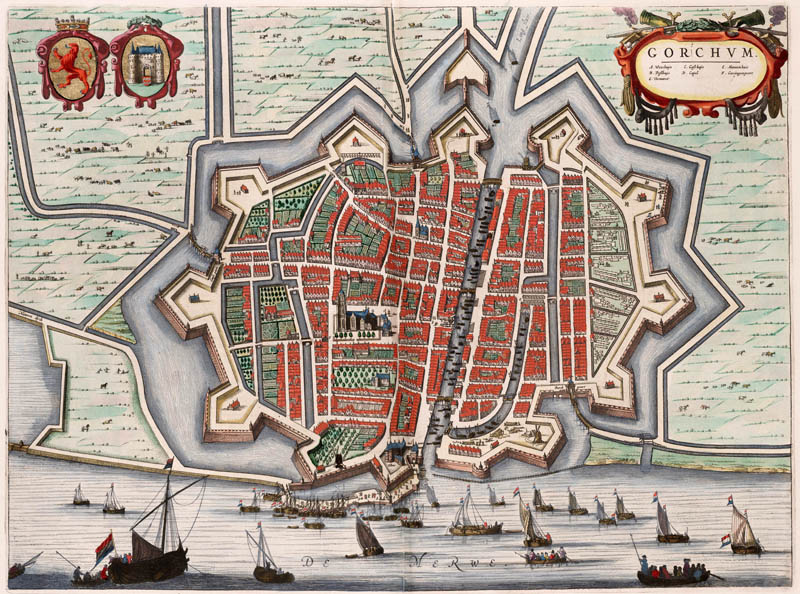

Gorinchem

The first written mention of Gorinchem dates back to 1224. In that year, Floris IV of Holland granted the local residents exemption from tolls in his county. Gorinchem, located at the confluence of the Linge and Merwede rivers, quickly became a hub for river trade. Positioned between Holland, Gelre, and Brabant, the Lords of Arkel were able to establish themselves as influential figures in the area (until 1407, when Gorinchem was transferred to the Count of Holland). In 1382, Otto van Arkel granted the town, which by then had around 3,000 inhabitants, an important charter. This charter regulated the jurisdiction of seven aldermen, and contained provisions on the city’s governance, annual fairs, and taxation.

In the following centuries, the town grew, reaching a maximum of around 4,500 inhabitants in the mid-fifteenth century, marking its economic peak. The core of this prosperity was driven by river trade, the cloth and brewing industries. Gorinchem was an important link in the toll policies of the region’s respective ruling lords, and frequently came into conflict with other towns along the river. Despite the difficult circumstances of the Dutch Revolt and the Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648), Gorinchem managed to more or less maintain its wealth, partly due to the large garrison of soldiers stationed there. After 1650, however, the town’s trades and industries began a slow but steady decline.

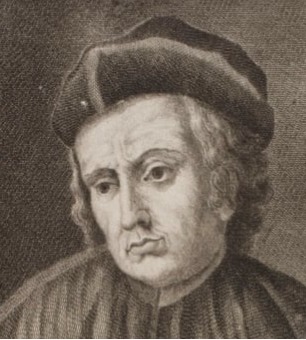

Lodovico Guicciardini

Descrittione di tutti i Paesi Bassi

(1567)

< ‘Gorinchem hath alwayes maintained a verie great market of cheese, butter, and other victuals, insomuch that an uncredible quantitie of sundrie wares is daily seene to be borne forth from this towne unto other places, most speciallie unto Antwerp. Wherefore the burgers and inhabitants grow exceeding wealthy, for they be themselves both merchants and mariners, conveying their own goods with their own vessels.’ >

Law and Governance

According to the charter of 1382, the city government consisted of seven aldermen and two burgomasters. The latter had been in office since at least 1349. New aldermen were appointed annually (in consultation with the retiring aldermen) by the lord. Their main task was jurisdiction. At their head was a sheriff (schout). During the Arkel Wars (1401-1412), the urban government was forced to transfer the city to the Count William VI of Holland, who, upon his inauguration in the city, granted Gorinchem an additional charter with far reaching concessions.

This incorporation into Holland led to the appointment of a bailiff (drossaard) as the local representative of the count. He also acted as dike warden (dijkgraaf), assisted by seven ‘high home-advisers’ (hoogheemraden). In addition to the bailiff, the city government consisted of a council counting seven aldermen and seven councillors. This council elected two burgomasters from among its members for executive and administrative duties. Only the most prominent citizens in terms of wisdom and wealth were eligible for these positions, and they had to be citizens for at least two years.

Formally, Gorinchem did not possess the right to issue bylaw (keuren), but the city semi-autonomously established many regulations. Possibilities of public participation in the government, for example through guild representations, were probably limited. In 1454, dissatisfaction among citizens over the city’s finances and their obligations to the lord, triggered Duke Philip the Good to introduce five treasurer (tresorier) positions. However, in 1516, these treasurers had become so controversial that a commission of the Court of Holland advised the city to reduce their number to two. They were appointed for five years, had a fixed salary, were prohibited from holding other positions, and were required to report within a term of three months.

During the same period, several urban administrative offices were developed. In 1414, the first city messenger was mentioned. Two years later, it is known that Jan van Kalker held the office of city writer, which gradually evolved into the position of urban secretary. By 1457, Dirk van Leuven held this position, and from the period 1500-1560, five secretaries are known by name. Thereafter their number gradually increased to three in 1757. Especially in the seventeenth century, the city’s secretaries received legal training: more than half the officeholders held a title. Later the proportion of jurists decreased, and it became more of an honorary position (at least for one of the two). The secretaries were assisted by a clerk. As of 1504 (but perhaps earlier) the city also employed a pensionary who advised the city in legal matters. Given their legal background, durable involvement in urban governance, and extensive network, the pensionary could potentially gain a strong power position.

Under King Philip II of Spain, efforts were made to organise the urban government more efficiently. A 1557 regulation was revised into a final ordinance of 1564. From this period, for example, stems the extension of the city council (vroedschap) to 24 members, and the election method of the aldermen: the bailiff, as representative of the sovereign, selected seven new aldermen from a list of fourteen compiled by the sitting aldermen. The Dutch Revolt, however, caused much unrest in Gorinchem. In 1572, the city joined the other rebellious cities. From the perspective of urban governance, little changed. The revolt sought to restore local rights and privileges. About 15 family names appear in the in the magistrate list before and after 1572. About ten names disappeared after 1572, while seven reappeared after the Pacification of Ghent (1576). Only a few new names appeared on the list after 1572.

The city government continued to exist of a bailiff, who was in principle appointed for life. The council normally included two burgomasters, seven aldermen, a treasurer, and a building overseer (fabriek) as well. This body, with small and temporary changes, remained into place until 1795. Council members held their seats for life. Replacement occurred through a nomination of three candidates by the council itself. Initially, the States of Holland, but later the Stadtholder, after consultation of the bailiff, selected the new members. During the stadtholderless periods, the leading regent families took the opportunity to appoint members by themselves. Younger council members gained experience by serving a year as building overseer and a year as treasurer. The first was involved in supervision of housing projects and maintenance of the urban infrastructure. The second managed the city’s accounts. In 1661, the position of receiver (ontvanger) was created, changing the treasurer’s role into a more supervisory one. The burgomasters had ultimate responsibility for the finances. They were elected by the Stadtholder from a nomination of three drawn up by the fourteen sitting and retiring aldermen. Burgomasters typically served for two years (but some served many terms, at times consecutive). In 1661, the city council also claimed the right to elect the aldermen, which was regarded as an infringement of the established custom that retiring aldermen elected their successors. The Court of Holland finally decided the conflict in favour of the latter’s view, and annulled the council’s decision.

Illustration: Salomon van Ruysdael, Schepen op de Boven-Merwede met Gorinchem op de achtergrond (1659).

Gorinchem had two shipmasters’ guilds: owners of ships larger than eight last (approximately 2,000 kilograms) could join the large shipmasters’ guild (grootschippersgilde), while those with smaller vessels could join the small shipmasters’ guild (kleinschippers– or schuitenvaardersgilde). In 1621, Gorinchem had at least 29 shipmasters, likely including ten members of the large shipmasters’ guild. The seventeenth century also witnessed the rise of market and ferry skippers who operated exclusive routes on fixed schedules. By 1677, such routes connected Gorinchem with ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Dordrecht, The Hague, Gouda, Leiden, Rotterdam, and Zeeland.

Economy

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the economy of the Gorinchem region was mainly focused on agriculture and cattle farming. The products were sold on the Gorinchem market, making the agricultural sector an important driver of its initial phase of economic growth. The strategic location of Gorinchem at the confluence of the Linge and Merwede played a significant role in the commercial development of the city. Early on, the city found itself in conflict with Dordrecht regarding the latter’s staple rights. These rights required goods to be offered for sale in Dordrecht before they could be traded elsewhere. From 1360, regulations began to improve under Otto van Arkel. During this period, the city expanded across the harbour. By 1352 a grain mill was established and in 1365, wealthy merchants from Liège and Cologne settled in the city to engage in the trade of grain, stone, and lime.

In 1382, Gorinchem was granted the right to organise six annual fairs: three general fairs, a horse market (likely also a hub for cheese trade), a livestock market, and a cloth market. This highlights the city’s supra-regional economic function during this period. During the fairs, market tolls were levied, and during the Whitsunday fair, a special water toll was imposed: skippers transporting more than four voeder (approximately 3,500 liters) of wine were required to pay six shillings (exceeding the daily wage of a skilled labourer). To ensure product quality, the city started to employ several inspectors (vinders) to oversee goods sold at the markets and in the urban shops – which was particularly crucial in the meat trade.

To facilitate loading and unloading activities, the city (in cooperation with Otto van Arkel and a certain Heynric Poker) established a crane at the Lingehaven, which was leased to a crane master as of 1395. The crane master was authorised to collect crane fees: while skippers were permitted to unload goods themselves, they were still required to pay half the crane fee. For wine, however, the use of the crane was mandatory. On unsold wine, only half the crane fee was charged. As a result, it became customary to invite potential buyers onto a ship to finalise the transaction, thereby shifting the crane fee to the buyer.

During this period, the first guilds were founded as well. The oldest was the cloth merchants guild. In 1392, they were granted access to their Gewandhuys (cloth hall), where they were required to sell their fabrics on Mondays. However, Gorinchem would never evolve into a true textile city like Leiden or Haarlem. Other significant economic activities likely included beer brewing – an industry that would become the most important in the city –, and brick- and tile manufacturing.

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, river trade further expanded, partly aided by Gorinchem’s improved competitive position following the St. Elizabeth’s Flood of 1421. Skippers transported local products such as beer and cloth, but primarily goods produced elsewhere, such as salt, cheese, timber, herring, and stones. From early on, citizens had enjoyed toll exemptions in Holland (as of the early thirteenth century) and Brabant (1287/88). Even in the fourteenth century, when Dordrecht’s staple rights were expanded, this still provided many opportunities for clandestine trade.

In the second half of the fifteenth century, the city’s economy began to decline, primarily as a result of the Guelders Wars and the competition of cities such as Delft and Gouda. As early as 1454, the city council reported that the city was in financial distress. Although significant investments were made at the beginning of the sixteenth century to dig a new waterway to improve access to the city harbour, it appears that Gorinchem’s economic peak had passed.

The Dutch Revolt was a challenging period. Wealthy citizens often relocated to Amsterdam. Nevertheless, even after hostilities ceased, the city continued to host a garrison, typically comprising a few hundred soldiers along with their entourage – wives, children, couriers, and prostitutes. This presence generated significant additional economic activity. Refugee merchants and artisans from Antwerp and other cities also settled in Gorinchem, particularly cloth and pin makers. Between 1570 and 1590, the city welcomed as many as 300 new citizens. However, while the pin-making industry initially flourished with the establishment of a guild in 1576, it was already in decline by the 1590s. Another lucrative business in this period was coin forgery, as a result of the fact that Gorinchem had its own mint between 1583 and 1591.

In the seventeenth century, the primary economic sectors remained river trade and beer brewing. By 1597, Gorinchem already counted 17 breweries, even if most of them appear to have been relatively small. The 1640s and 1650s can be identified as the peak period for the breweries, with their number increasing to 24, mostly located along the Langedijk/Eind (8), Appeldijk/Kriekenmarkt (4), and Westwagenstraat (4-5). The brewers were organised into a guild, probably around 1598. The brewers sourced water from the city’s canals, often leading to disputes with tanners and shoemakers, who polluted the water. In response, the city council restricted the soaking of hides and washing of hair to areas outside the Arkelpoort.

Other crafts were also found in the city during the seventeenth century, including bombasine production, glassblowing, vinegar production, pipe making, and soap boiling. Even so, the city’s economy fell behind. After 1700, Gorinchem faced a general decline, reaching its nadir around 1740. By approximately 1690, the number of tanneries had decreased from 30 to 3, and by 1786, the number of breweries had fallen to 4.

Sources

- The best modern introduction to the history of Gorinchem is F. Cerutti et al (eds.), Tien eeuwen Gorinchem. Geschiedenis van een Hollandse stad (Utrecht, Matrijs, 2018).

- A smaller and online available introduction is B. Stamkot, Geschiedenis van de stad Gorinchem (Amsterdam, Stichting Merewade, 1982).

- For the rural economy in the Gorinchem region, the best work to start with is probably B. van Bavel, Transitie en continuïteit. De bezitsverhoudingen en de plattelandseconomie in het westelijke gedeelte van het Gelderse rivierengebied, ca. 1300-1570 (Hilversum, Verloren, 1999).

- Printed medieval historical sources can be found in H. Bruch, Middeleeuwse rechtsbronnen van Gorinchem (Utrecht, Kemink, 1940) (available online).

- Trade conflicts with Dordrecht are particularly studied by J.F. Niermeyer, ‘Een vijftiende-eeuwe handelsoorlog: Dordrecht contra de bovenlandse steden, 1442-1445’, Bijdragen en mededelingen van het historisch genootschap 66, 1948, p. 1-59 (available online).

- Older relevant historiographies of Gorinchem include: Cornelis van Zomeren, Beschryvinge der stadt Gorinchem en Landen van Arkel (Gorinchem, Horneer, 1755) (The book, however, is written earlier: Van Zoomeren died in 1707. Available online); Abraham Kemp, Leven der doorluchtige Heren van Arkel ende jaarbeschrijving der stad Gorinchem (Gorinchem, Vink, 1656) (available online); Theodoricus Pauli (transl. H. Bruch), Kronycke des lants van Arckel ende der stede van Gorcum (Middelburg, Altorffer, 1931) (available online).

- An inventory of the judicial archival sources available in the Regional Archive Gorinchem can be found here: [link]. For, archival sources concerning (mainly seventeenth century) guilds, an inventory can be found here: [link].

dr. Marco in ‘t Veld

Author