Schoonhoven

Schoonhoven’s origins can be traced back to at least 1233, when Floris IV, count of Holland, ordered the construction of a substantial dike between Amerongen and the town. Almost half a century later, in 1280, the city already had its own aldermen and law court. That same year, Count Floris V granted it the right to seize debtor’s goods throughout Holland. In 1322, Schoonhoven was freed from its feudal bonds by Count William III of Holland and received the right to issue local bylaws (keurrecht) from John of Beaumont (William III’s younger brother, the lord of Schoonhoven). This established Schoonhoven’s legal autonomy though appeals in court cases still went to Dordrecht.

Over the following centuries, Schoonhoven became a modest but active market centre for its neighbouring towns. Dairy industry, silversmithing, and regional shipping formed the backbone of the local economy. The River Lek (a continuation of the Nederrijn, a distributary branch of the River Rhine) provided access to wide trade networks, connecting Schoonhoven to for example Gouda, Rotterdam, and Dordrecht. A scheduled shipping service (beurtvaart), developed in the first half of the seventeenth century, ensured a steady flow of goods and passengers, sustaining the local economy well into the eighteenth century. A window of opportunity for extra economic growth was opened in 1535, when the town secured an imperial license for a dairy market. However, this chance was only short-lived, as legal conflicts with Gouda ended the market in 1540. From the Middle Ages onwards, and especially after the founding of the Silversmiths’ Guild in 1615, the city built a strong reputation for fine metalwork. By the late eighteenth century, Schoonhoven’s prosperity was waning. Larger cities outpaced its trade and industry, and guilds lost influence. The silver industry did earn Schoonhoven the title ‘Silver City’, a name it proudly carries to the present date.

Thomas Daniel Moor

Schoonhovensche Arcadia

(1783)

< ‘Who, O noble Lek-stream, can rightly praise thy worth?

What scenes of Pleasure and of Greatness here arise,

To charm the eye! For Nature, in her plain simplicity,

Doth there outstrip the artful hand of Man,

And spreadeth all about a Lustre none may paint.’ >

Law and Governance

A charter shows that the lordship of Schoonhoven already possessed high justice in 1280, meaning that corporal punishments could be inflicted upon a convicted person. Aldermen were elected from its citizens (poorters) to serve in the local court. As mentioned, they got the right to seize the goods of debtors anywhere in the County of Holland, in which they were assisted by the count’s bailiffs (baljuws) and sheriffs (schouten). The bailiff was the representative of the count within the larger bailiwick, whereas the sheriff served as the representative of the count within the city itself. On 4 May 1322, Schoonhoven was freed from its feudal bonds (and therefore legally separated from the surrounding area) by Count William III of Holland and became a free city. Two months later, John of Beaumont granted the city the right to issue local bylaws, thus further extending the autonomy of the urban authorities. Nevertheless, the urban privileges of Schoonhoven were modelled after the example of Dordrecht. The latter city also held the both the right to advice the aldermen of Schoonhoven in complex legal cases, and the right of appeal in cases decided in first instance in Schoonhoven.

In 1322, the city was governed by a sheriff (schout), seven aldermen, and two burgomasters. The city council (raad der poorte), with an undefined number of members, represented the entire community. According to Van Berkum, they had the right to advise and decide on all matters concerning the city. In 1356, Jan II of Blois, lord of Schoonhoven, obliged the aldermen and councillors to have lived in the city for at least six years and to own property worth at least 100 pounds Hollands to be eligible. In 1412, this requirement was further extended. Henceforth, the sheriff, aldermen, and burgomasters were required to own a horse worth at least eight nobles within six weeks after taking office. Economically, the city also became more independent from its lord, as he sold the town windmills and wind rights in 1356. It took until 1440 before three treasurers (tresoriers) were added to the urban government to manage the city’s income and expenditures.

Law-making in Schoonhoven followed a system according to which bylaws involving fines higher than five shillings were issued by the bailiff, the seven aldermen, and two burgomasters, while bylaws involving fines less than five shillings were drafted by sheriff and aldermen in cooperation with the city council. In court a different distinction was made, namely between the higher jurisdiction, concerning criminal law, corporal punishment, and major disputes, and the lower jurisdiction, handling civil cases of lesser value, questions of public order, and minor offences. The seven aldermen formed the core of the city’s government and exercised both the higher and lower jurisdiction, while the bailiff and sheriff presided over respectively the higher and lower court, representing the lord’s authority.

In times of political unrest, the city of Schoonhoven prioritised the safety and neutrality of the city. In the turbulent year 1417, during the succession crisis around Countess Jacoba of Bavaria, the town refrained from participating in military actions such as the siege of IJsselstein. This neutral status made it a suitable location for the assemblies of the States of Holland: until 1515 the city 73 times served as host of these dagvaarten. The city was invited to participate in such meetings 468 times, a high number that shows that it was treated as a full member of the States of Holland despite its modest size. This participation brought political influence beyond the city walls. To support its delegates at such meetings, the city employed a single secretary (secretaris), who also performed the duties which in larger cities came to be handled by a pensionary. Some of these secretaries were lawyers, which carried extra weight in negotiations, although most were not, and the academic qualification was not strictly required for the function.

In 1480 the sheriff, aldermen, burgomasters, and city council of Schoonhoven were granted the right to annually elect 27 noble and competent persons on the 4th of November. They would then nominate candidates to be elected as next year’s aldermen and burgomasters. To be eligible, candidates had to meet a property requirement of at least 300 Rhenish guilders. For the first time, it was formally recorded that two burgomasters and seven aldermen were to be appointed annually. However, in 1542, the Emperor Charles V transferred the right to draw up the annual list of candidates back to the retiring burgomasters and aldermen, thereby reversing the 1480 privilege. Fourteen years later, Philip II reinstated the 1480 system with 27 electors.

During the Dutch Revolt, the city was captured by the watergeuzen in 1572. In 1575, the city was besieged by Gilles of Berlaymont, in service of the Duke of Alba. In 1577 the city definitively came under the authority of Prince William of Orange as stadtholder of Holland. He appointed a new bailiff and sheriff. The city was allowed to raise its excise taxes and to suspend its payments to the States of Holland for three months. The burgomasters and aldermen all swore an oath of loyalty to the prince. In 1581, following the Plakkaat van Verlatinghe, all officials and militia members had to take a new oath and pledge to act against Philip II.

In later centuries, during internal conflicts such as the early seventeenth-century disputes about religion and international politics (the Bestandstwisten), Schoonhoven’s magistrates took active measures to protect the city’s autonomy and order. A notable step was the hiring of waardgelders (paid soldiers) to maintain order within the walls and to deter interference from outside. These measures reflected the determination of Schoonhoven to preserve both its privileges and the safety of its citizens.

By the seventeenth century, Schoonhoven’s authorities controlled many urban offices. Their appointment rested entirely with the town magistrates. Each year they appointed for example the governors of the urban ecclesiastical and charitable institutions: churchwardens, Holy Ghost masters, hospital masters, etc. They also filled or reassigned the other small offices. These officials were accountable to the burgomasters and had to submit an overview of the institution’s real estate assets to the secretary. This prevented abuses during their term of office. The burgomasters were also in charge of the appointment of the guild deans. In the seventeenth century, the city twice provided a stipend for a young citizen to finance their study: one for theology at Leiden University, and one, probably in philosophy, at Utrecht University.

Although subject to the States of Holland and the authority of the stadtholder, Schoonhoven’s magistrates took great care to safeguard the towns long-standing privileges, charters, freedoms, and exemptions, many of which had been granted by former lords and confirmed by the Counts of Holland before 1581. When they believed these rights were curtailed, the urban magistrates petitioned the higher authorities to have them confirmed, approved, and maintained. Schoonhoven, for example, was one of the leading cities in the centuries-long persistent resistance against Dordrecht’s staple rights. In the surrounding countryside, legal authority was shared with the regional nobility, but within the city walls the urban authorities exercised full control over justice, markets, fortifications, and public works until the end of the ancien régime.

Illustration: Simon Bening’s studio, A man on a ladder ties vines to arches. Miniature from the Da Costa Book of Hours (c. 1515). © The Morgan Library & Museum, New York.

Vineyards were rare in the Northern Low Countries, as the climate was generally far from ideal for viticulture. Nevertheless, between the mid-1360s and the end of the fourteenth century, vineyards flourished in the gardens of Schoonhoven’s castle, first under Jan II of Blois and later under his brother Guy II of Blois. Offering wine to guests was an expected mark of generosity. The mere presence of vines, often trained along elegant pergolas, projected the image of wealth and refinement, even if those vines rarely yielded drinkable wine.

In Schoonhoven’s case, the vineyards were used to produce verjuice, a highly acidic juice made by pressing unripe grapes. This was an ingredient used to enhance certain dishes served to the lord’s guests. The castle’s gardener oversaw the annual harvest and pressing, producing several hundred liters a year. From an economic point of view this was not very profitable, although it was no more costly than importing verjuice from established wine regions. It ensured a fresh and reliable supply to the castle’s kitchens. Since production at times exceeded local needs, it is possible that some of the verjuice was traded as well.

Economy

Already in 1280, the city of Schoonhoven acquired exemption from the river tolls in Holland as part of a charter of urban liberties. Thereafter, the city greatly benefited from its location on the River Lek. It had particularly good water connections with Gouda, Rotterdam, and Dordrecht. Therefore, the city functioned as a regional hub for the river trade, which created significant employment opportunities in logistics and attracted merchants as well as market visitors. Shipping and transport were important pillars of Schoonhoven’s economy. The privileges of 1280 granted the city the right to levy tolls on visiting merchants. In the early phases of the city’s existence, dairy products and cloth were the most important traded products. The city witnessed its strongest growth from the late thirteenth century to the years around the urban fire of 1375. From the mid-fourteenth century onward, comital accounts record a shifting calendar of fairs, including markets for poultry, horses, and cattle, each lasting fourteen days and protected by safe-conduct. Although Schoonhoven’s citizens claimed to be hindered by the Dordrecht staple, the city cannot have been held back too much, since both dairy and cloth were exempt from the Dordrecht staple.

Schoonhoven fostered the ambition to become a staple town itself, although its strategy was to be less strict than Dordrecht. Merchants would then naturally prefer Schoonhoven over Dordrecht. However, the city on its own remained too small to become a serious economic threat to Dordrecht. When collaborating with other cities, however, it could turn into a dangerous opponent. In the middle of the fifteenth century, Schoonhoven took advantage of a conflict between Dordrecht and some cities in Guelders and the Rhineland. As these cities boycotted Dordrecht, Schoonhoven was delighted to welcome their merchants, instead. Despite the conflict, Dordrecht maintained its staple rights. The enforcement of these rights was never watertight, and Schoonhoven was never entirely pushed out of the interregional river trade and transport.

A skippers’ guild existed at least after 1607, when it offered a large plaque to the Reformed church. To ensure smooth shipping operations, in the seventeenth century a scheduled shipping service was installed connecting major cities. The skippers’ guild maintained a regulated system to safeguard fairness and continuity, using a beurtrol to record who was assigned to sail at what day and time. When a skipper refused to depart on his turn, he could be fined. Prices of transport were fixed, to prevent shippers from offering transport under the market price. The guild feared that individual shippers would otherwise gradually drive down the average prices. The beurtrol also guaranteed a consistent influx of goods, both for consumption in the city, and for resale to other merchants.

Apart from the shipping industry, another important pillar of Schoonhoven’s economy was its dairy industry, mainly producing cheese and butter. The city was also active in hemp cultivation and oil production. These products were traded locally. Export was easy because of the town’s extensive shipping activity and beneficial geographical location. An important moment was the attempt to establish a cheese market as a copy of the large Gouda cheese market. The urban government thought that this would drive the city’s economy forward. In 1535, Schoonhoven received a charter from Emperor Charles V allowing the organisation of a cheese market. However, Gouda, fearing competition, filed a complaint with the Great Council of Malines to prevent this. A lengthy and expensive lawsuit followed. Gouda persisted, while it possessed greater resources and political influence. Schoonhoven eventually gave up, which was an economic setback, particularly at the local market level.

Schoonhoven was also known for silversmithing, its reputation extending far beyond the city’s borders. Its silver industry had great economic value. In relation to its population, Schoonhoven counted many silversmiths. In 1615, they organised themselves in the Guild of Silversmiths. The guild had its own quality mark and regulations. It oversaw the professional training, masters’ examinations, and the enforcement of product standards. The establishment of the guild marked the beginning of a long-lasting period of economic success for the local silver industry. Even when other cities gradually overshadowed Schoonhoven during the eighteenth century, the silver industry continued to be an important economic branch that brought the city a strong reputation in the Dutch Republic and beyond.

This, however, could not prevent the city of Schoonhoven from ultimately losing its economic position. In the long term, it could not continue to successfully compete with larges cities such as Dordrecht or Rotterdam. As a result, its shipping , dairy industry, and linen trade were all declining by the eighteenth century.

Sources

- The best modern introduction to the institutional history of Schoonhoven is: P. Niestadt & R. Kappers, Het leven in Schoonhoven. De geschiedenis van het bestuur van de stad (Schoonhoven, Stichting Historische Uitgaven, 2014).

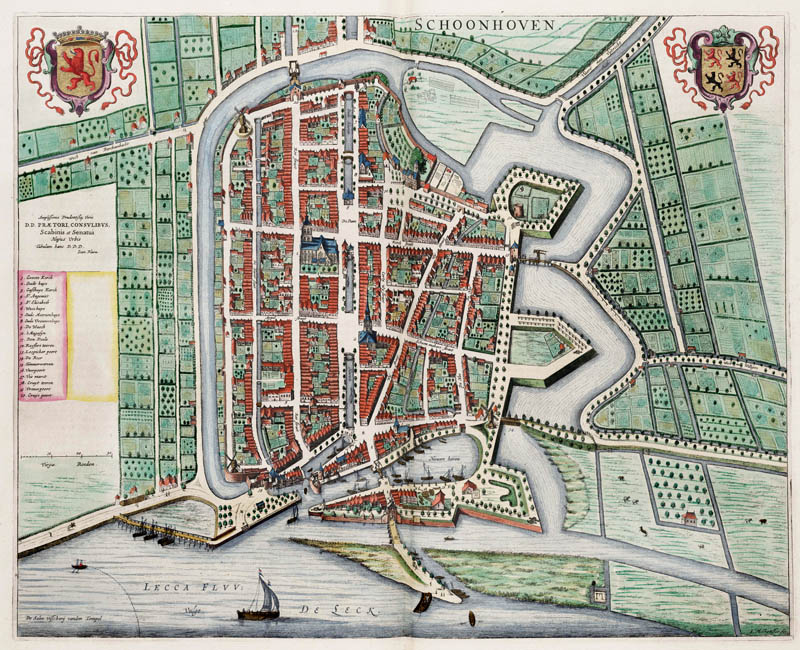

- The city’s spatial development has been researched by: J.C. Visser, Schoonhoven: de ruimtelijke ontwikkeling van een kleine stad in het Rivierengebied gedurende de Middeleeuwen (Assen, Van Gorcum, 1964).

- Many modern publications are still very dependent on: H. van Berkum, Beschryving der Stadt Schoonhoven … (Gouda, Gijsbert en Willem de Vrij, 1762).

- The viticulture around Schoonhoven was studied by: M. Breukers, ‘Boven de 50ste breedtegraad. De middeleeuwse wijngaarden van Schoonhoven’, TSEG 2023-2, pp. 5-32.

- Information on Schoonhoven’s economy can be found in: J. Dijkman, Shaping Medieval Markets: The Organisation of Commodity Markets in Holland, c. 1200 – c. 1450 (Leiden, Brill, 2011).

- Schoonhoven’s medieval and early modern archives (inventory number 1011) can be found in the Archief Midden Holland (in Gouda): [link]. It seems particularly rich on the many conflicts with Dordrecht. The judicial archives have another inventory number (1058) and go back well into the sixteenth century: [link].

dr. Marco in ‘t Veld

Co-author

Wenneke Bos

Co-author